The following are excerpts from essays to be published in the forthcoming book, Biodesign Challenge: A Retrospective. Selected from hundreds of artworks and designs from the Biodesign Challenge (BDC) competition, the book is a compilation of projects and ideas that are influencing the emerging field of biodesign. In their own words, pioneers and BDC alumni explore the future of biodesign and its role in shaping people’s identities, cultures, and relationships with the living environment.

The book is being published by Biodesign Challenge and can be pre-ordered through Kickstarter until July 20. Keep reading for a preview of three entries that caught our attention, from new materials made from crop waste to familiar rituals powered by bacteria.

Denimaze

Team: Julia Bell, Natalia Cabalceta, Saif Khawaja, Alina Peng, Mengda Zhang

Instructors: Orkan Telhan | Institution: University of Pennsylvania

Fabricating denim is a water-intensive process, requiring about 2,000 gallons of water to make just one pair of jeans. Harsh chemicals, synthetic dyes, and unfair labor practices are also common in traditional production, making the denim industry generally unsustainable. Students from the University of Pennsylvania decided to turn the byproduct of corn—an overabundant commodity in the United States—into an upcycled resource for making jeans. Their project, Denimaize, uses the 250 million tons of corn husks created each year and “diseased” crops to create denim from a blend of cotton and corn waste. They created a blue dye derived from cultured plant pathogens and algae commonly growing in eutrophic sites from fertilizer runoff. The goal is to build a circular system between corn agriculture and the fashion industry.

From the essay: “The project began when we visited a farm in New Jersey to learn more about corn processing. There we learned that diseased crops, specifically corn with the Ustilago maydis fungus, commonly known as corn smut, are burned to contain infection. But not all cultures view infection as problematic. In Mexico, for example, corn smut is a delicacy known as huitlacoche. For Denimaize, we wanted to challenge the negative associations of infection by exploring how diseased cornhusks could be used for new purposes—in this case, textiles.”

Denimaize, University of Pennsylvania, 2019

Pulmō Plastics

Team: Marian Shaw, Kathy Wu

Instructor: Stefani Bardin | Institution: New York University

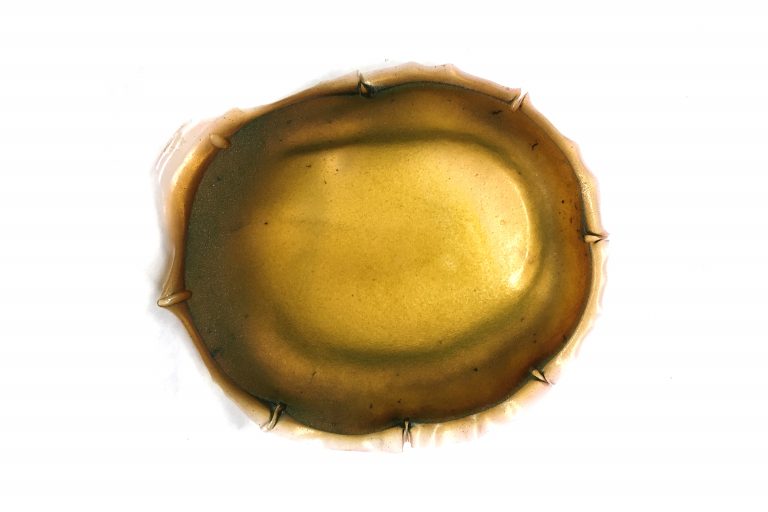

Jellyfish are overwhelming the world’s oceans. They proliferate at a very high rate when exposed to warmer waters, and can pose a threat to ecosystem balance. However, this abundance may be an opportunity to create a new biomaterial. Students from New York University discovered that the high-collagen content of jellyfish make them a suitable ingredient for creating bio-based plastic. Their product, Pulmō Plastic, speculates a near-future where decomposing jellyfish biomatter is used to produce materials that can replace petroleum-based plastic polluting the ocean.

From the essay: “Jellyfish are mostly made of collagen. We proposed to use jellyfish collagen as a raw material for food-safe, biodegradable plastics. In our initial experiments, we created samples with varying material properties: gelatinous like silicone, firm like a soda bottle, brittle like glass, and supple like a plastic bag.”

Pulmō Plastic, New York University, 2018

GIY Bio Buddies

Team: Anne Hu, Trisha Sathish, Emily Takara

Instructor: Corinne Okada Takara | Institution: Nest Makerspace

The average toy fad lasts just 8 months. But the lifespan of the materials used to make those toys is much greater—sometimes up to 450 years. As a way to reduce plastic use, a group of students from Nest Makerspace designed a kit that allows kids to grow their own toys. The kit, called GIY Bio Buddies, GIY short for “grow-it-yourself”, doubles as an educational resource for young makers to get hands-on experience with materials like SCOBY and mycelium. These biomaterials, grown from bacteria and fungi, can biodegrade within a few weeks, reducing the plastic footprint of post-use toys.

From the essay: “We created GIY Bio Buddies because we believe that the toys that define childhood should not harm the environment. The idea emerged while we were growing kombucha leather and mycelium for our afterschool biodesign program. Since we enjoyed this growing process, we wanted to replicate the joy of exploration for others. It’s not just plastic that we wanted to replace; we wanted to create an experience.”

GIY Bio Buddies, Nest Makerspace, 2019

Top image: Pulmō Plastic, New York University, 2018. Courtesy of Biodesign Challenge.